Thanks Jeff, for calling me out, otherwise I might never have blogged again.

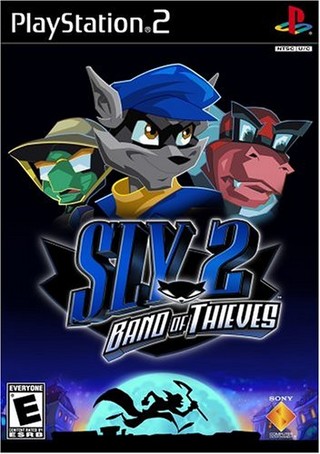

Back when I wrote my post about Games of My Life, I had intended to go back and break down each one and say why it was so impactful. This is belated, but I’m going to get started now. In honor of tomorrow’s re-release of The Sly Collection, I’m going to start of with Sly 2: Band of Thieves, which I’ve previously referred to as “the most perfect and under-discussed game of the 2000’s.” A bold claim, and it’s time to back it up.

Like most game designers, I like to think of the game experience in levels, from the lowest (I am pressing a button to jump) to the highest (I am trying to stop the Klaww Gang from reassembling Clockwerk) and everything in between (I am trying to get to to the end of this level, I am collecting money to buy an upgrade, et cetera).

Sly 2 provides an almost impeccably balanced experience at each of these levels, and, most impressively, manages to have them reinforce each other and support the emotional themes of the story.

Run ‘n’ Jump

At its heart, Sly 2 is a cartoony action platform game. The team at Sucker Punch has shown themselves to be incredibly skilled at creating smooth, flowing control for such gameplay, and making your anthropomorphic raccoon1 zip through the world is effortless.

Contrast this with the control of Sam Fisher in the Splinter Cell games. Sam is supposed to be a hyper-capable secret agent who single handedly saves the world, yet I could not for the life of me make him consistently do a wall split. Instead he flails about bouncing off the walls until the guards come and investigate him. Not very sneaky, Sam!

(Which one of them would win in a fight? Depends on whether I’m the one controlling them.)

Sly 2, like its predecessor, provides blue sparkles through the world where you can simply press the circle button to have Sly automatically do a thief-y move at that location. You can argue that this is dumbing down the gameplay, or the mark of a kiddie game. I argue that it’s making my onscreen avatar’s behavior match his authored character more closely.

At the lowest level, Sly 2 is almost identical to the first game in the series. So why do I hold it up? For that, we need to look at what it changed.

I Can See For Miles

The biggest shift between the first Sly Cooper and Sly 2 is the move to open worlds instead of linear levels. Each world is the area around the home base of one of the villains, and your goal there is pull off a big heist and steal the Clockwerk piece that they possess. The worlds are elaborately structured so that you do a series of prep-work (taking recon photos, sabotaging alarm systems) before the final caper. There’s some innovative planning here that would put Danny Ocean to shame.

All these objectives are laid out to you with a series of bat-signal-like beacons projecting into the sky — this activates the “cleanup/gotta catch’em all” compulsion loop in a fundamental way. Seeing them blip out as you complete each objective is rewarding to the lizard brain.

This is also where the layers of gameplay come in handy — Sly 2 gets away with highly repetitive gameplay at one layer (you spend a lot of time pickpocketing keys, for instance) by having the lower layers polished (the simple but very predictable stealth system) and the higher layers varied (why you need the keys).

Lets Do the Twist

What keeps bringing me back to Sly 2, though, and why I play it probably once a year, is the way it unfolds its story. The characters are compelling and familiar tropes from Saturday morning cartoons. But there is such care given to the writing of those characters that it retains the feel of some of the best cartoon shows. This is closer to Kim Possible than SpaceCats (and if you don’t think that cartoons can be examples of quality writing, then we probably just don’t have much to debate). There is an unmistakable panache to the dialogue which indicates to me that someone on the staff cared about the writing immensely.

At the higher level, the story never forgets that it is a story for a game. The cutscenes are all payoffs for gameplay, and never include a moment that I wish I could have played out myself. Sucker Punch knows that when the cool stuff starts happening, I want the controller in my hands, and wisely gives me that agency.

Finally, the story toys with player assumptions with enviable prowess. As you start the third world, you feel like you’ve got the pattern down. Bentley gives you the plan with a slideshow, you carry out a bunch of missions, you do a big heist, boss fight, on to the next world. But just a few steps into the third big heist, things go horribly wrong. Everyone except Bentley (the weakest, slowest, character, who the player has likely not enjoyed controlling during his missions) is captured, the mission is aborted, and you’re sidetracked into a jailbreak mission without any of the skills you’ve honed.

It’s a great reversal from a story perspective, and the fact that the game strips away so many familiar mechanics simultaneously means the player’s emotional state (vulnerable, alone) matches the characters’. When you free Sly and Murray, each one feels like a tremendous burden lifted, and the joy the player feels at regaining access to a core gameplay feature mirrors the joy the friends feel at being reunited.

It matches gameplay mechanics to emotional story beats in a way I have seen no other game do nearly as consistently. Positively masterful.

And the Rest

I could go on. The consistent presentation (even the pause menu says “We’ll be right back!”), the superb level design of both the hub worlds and the individual mission areas (“no right angles”), the varying gameplay (even if the vehicle missions can get tiring).

Sly 2 is an exemplary instance of how to expand on solid gameplay concepts for a sequel while retaining what made the original worthy of continuation. The third game in the series was a slight let down, with a little too much gameplay variety and not as much polish on the plotting and writing. But that, too, serves as a lesson in design, and draws the successes of Sly 2 into sharper relief.

So why doesn’t anyone talk about this game? Maybe because it’s not seen as terribly innovative, or because it gets filed in with the kiddie games, or because its lack of difficulty means the hardcore players (which most designers are) stayed away. But just as I think most people would be fools to ignore quality movies or books because they are “kiddie fare,” the Sly Cooper series should serve as an example for how much craftsmanship can be stuffed into one experience. It may not do anything you haven’t seen before, but what it does is a paragon of execution.

1 I will say that one of the downsides of the game is that it attracts the love of furries. Nothing against furries, but it makes trying to find fan communities a bit more difficult.

-

I also felt this game is a great example of an open-world + platforming/stealth style game.

I think it’s overlooked because of the combination of:

- Being seen as a kiddie game

- Being such a hybrid of genres

- Not having the macho sex appeal of, say, God of War

Sad as it may be, that’s a deadly recipe for being overlooked by our rather myopic mass games media.

-

Good call, Darren. Sadly, I think it’s probably the third point more than any other.

I take some comfort in the fact that it was very successful sales-wise.

(The bullet points in your comment also inspired me to finally fix the CSS weirdness in this WP theme.)